Before we get to the adventures of Felis domesticus scholasticus promised by the title, some important background.

A couple of weeks ago, Nick Wise showed me an advertisement from a paper mill offering to boost the buyer’s citation count and h-index on their Google Scholar profile.

The advertisement links to several success stories consisting of unredacted “before” and “after” screenshots of clients’ Google Scholar profiles. These clients had apparently bought anywhere between 50 and 500 citations each. Of 18 apparent previous clients, 11 still had active Google Scholar profiles that we could visit. All identifiable clients were affiliated with Indian universities except for two: one client affiliated with a university in Oman and one client in the United States. Although the advertisement also mentions Scopus, we did not find evidence of this company successfully boosting these clients’ Scopus citation counts.

How was this company so effective at manipulating citation counts? For some clients, a wealth of citations came from dozens of papers in the same suspicious journal. These were probably papers on which the company had sold authorship. In one instance, the highest numbered reference in the text of the paper was Reference 40, while the reference list extended up to Reference 53. References 48 through 53 were to the client.

For most other clients, the scheme was more brazen. Inspecting citations to these clients revealed dozens of papers authored by such celebrated names as Pythagoras, Galileo, Taylor and Kolmogorov. The papers were not published in any journal or pre-print server, only uploaded as PDF files to ResearchGate, the academic social networking site. They had since been deleted from ResearchGate, but Google Scholar kept them indexed. Although the abstracts contain text relevant to their titles, the rest of the paper was usually complete mathematical gibberish. We quickly recognized that these papers had been generated by Mathgen (a few years back, Guillaume Cabanac and Cyril Labbé flagged hundreds of ostensibly peer-reviewed papers generated by Mathgen and its relative SCIgen).

At this realization, this company’s citation-boosting procedure fell into sharp focus:

- Get contracted by a client.

- Auto-generate several nonsense papers with Mathgen [Optional: change the titles and abstracts to something more plausible for the citation context].

- Insert citations to several of the client’s papers at a random point in the nonsense paper.

- Upload the nonsense papers to ResearchGate.

- Wait for Google Scholar to index the nonsense papers and their citations to the client.

- Congratulate the client on their newfound academic clout [Optional: delete the nonsense papers from ResearchGate].

This procedure was no-cost, low-effort and endlessly scalable. Nick suggested that anyone “can write a script to make the world’s most cited person/cat”. We had to try it for ourselves.

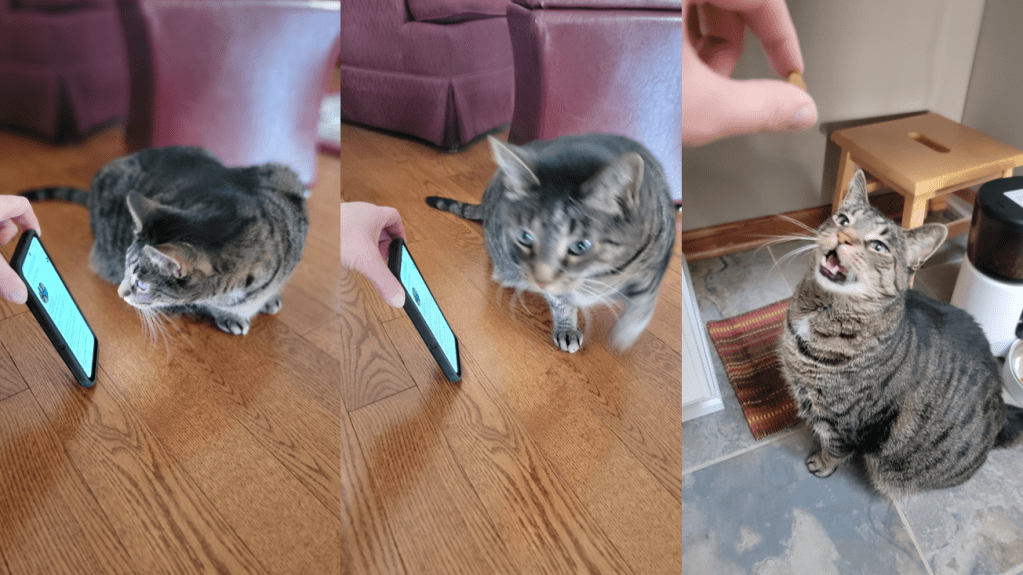

Now, we can finally introduce the hero of the story: Larry, my grandma’s cat.

Out of all the cats with human-ish names in our lives, “Larry Richardson” sounded the most like a tweedy academic and thus was a natural candidate for the title of world’s highest cited cat. As far as we could tell, the standing record-holder was F.D.C. Willard, a Siamese cat named Chester whose owner Jack H. Hetherington added him as an author on a physics paper because he had accidentally written the paper in the first person plural (“we, our”) instead of the first person singular (“I, my”). Chester went on to author one more paper and a book chapter under this name, which have since accumulated 107 citations according to Google Scholar. This was the bar to clear.

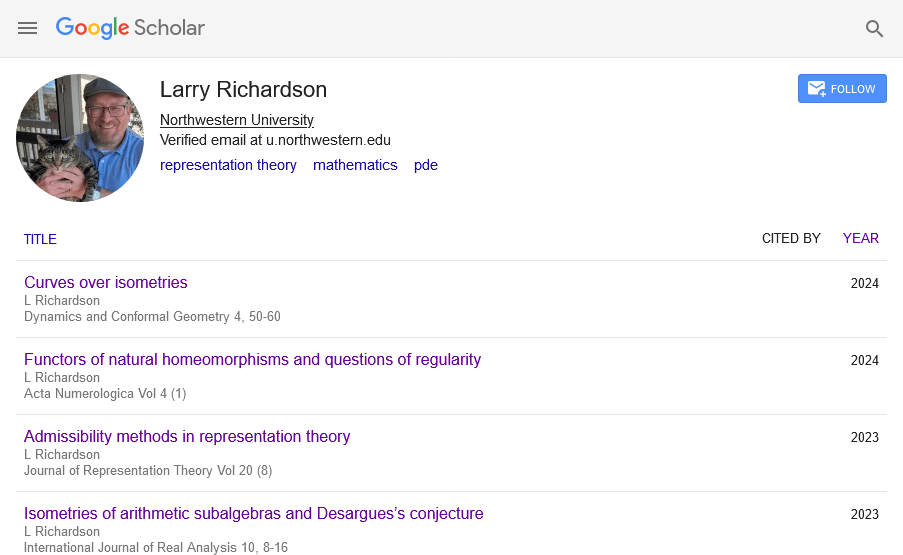

First, we generated 12 papers (using Mathgen) with Larry Richardson as the sole author. We then generated an additional 12 papers not authored by Larry, editing the LaTeX document of each paper so that each cited every one of Larry’s 12 papers (12 papers with 12 citations each = 144 citations with an h-index of 12).

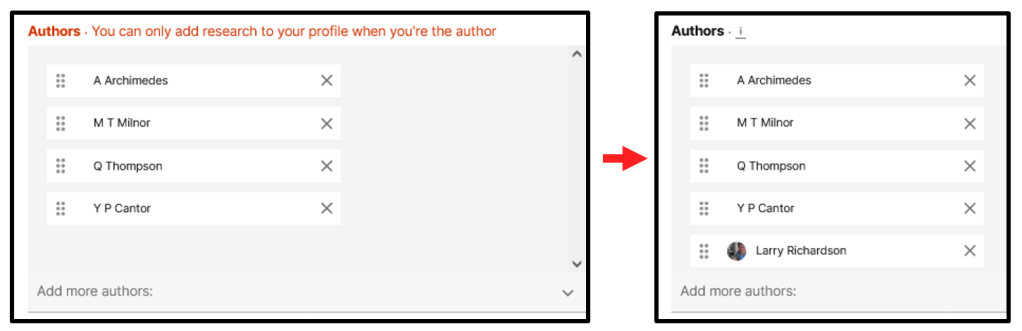

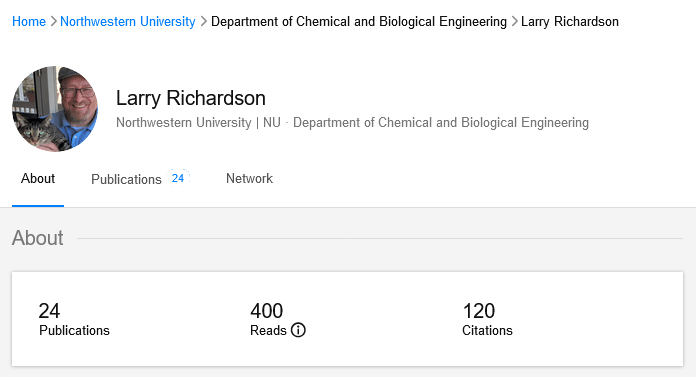

Next, we uploaded the papers to ResearchGate, all under the same profile. Anyone can make a ResearchGate profile, and if you use an academic email address, no additional verification is required. To avoid setting off alarm bells at ResearchGate by using the same academic email as my existing ResearchGate profile, I set up an alias northwestern.edu address for Larry that forwards mail to my existing account. Email accounts with a .edu top level domain are quite easy to come by (you can even buy one), so this ResearchGate security check does little to keep ne’er-do-wells out. The next security measure we encountered is that users can only upload papers that they have authored. Again, this security check was easily bypassed by just adding Larry as an author to the research item manually.

We then had to wait for Google Scholar to scrape and index these papers and their citations. Given that Google Scholar is known for indexing just about anything as an academic paper (up to and including school cafeteria menus), we had few initial doubts that the papers would be indexed shortly. However, for two agonizing weeks we regularly checked for progress, each time finding Larry’s profile empty. Nick and I began to suspect that we had done something wrong and the procedure for free citations was not as simple as it appeared. Then, just yesterday, our efforts paid off.

Larry Richardson is officially history’s highest cited cat (according to Google Scholar, at least).

While we aimed for 144 citations and only got 132 (one paper did not have any indexed citations for reasons we presently do not understand), we more than cleared the bar set by F.D.C. Willard and crowned Larry as the world’s most influential feline intellectual.

Of course, this isn’t about making a cat a highly cited researcher. Our efforts (about an hour of non-automated work) were to make the same point as the authors of this aptly titled pre-print: Google Scholar is manipulatable. Despite the conspicuous vulnerabilities of Google Scholar (and ResearchGate), the quantitative metrics calculated by these services are routinely used to evaluate scientists.

For a fairer scientific enterprise, we ought to ditch quantitative heuristics like citation count, impact factor and h-index altogether (see the Declaration on Research Assessment, DORA). Services like Google Scholar, Web of Science, Scopus and ResearchGate could bring us a long way towards this ideal by no longer providing these metrics to users. However, if these services are bent on keeping citation-based metrics around, they should at least make manipulating their products a little more difficult.

[ UPDATE: July 24, 2024 ]

As of this morning, Google Scholar has removed all of Larry’s original papers and citing papers and with them, his citations!

Larry held the title of world’s highest cited cat for exactly one week. His papers (and citations) remain intact on his ResearchGate profile.

Curiously, Google Scholar has not removed any of the fake papers citing the paper mill’s clientele. Google Scholar could still fix their part of the citation manipulation problem, but as of right now, they have instead taken targeted action against a cat.

[ UPDATE: August 1, 2024 ]

ResearchGate has now removed Larry’s profile and his papers. From Christie Wilcox’s coverage of Larry’s accomplishments for Science:

ResearchGate is “of course aware of the growing research integrity issues in the global research community,” says the company’s CEO, Ijad Madisch. “[We] are continually reviewing our policies and processes to ensure the best experience for our millions of researcher users.” In this case, he says, the company was unaware that citation mills delete content after indexing, apparently to cover their tracks—intel that may help ResearchGate develop better monitoring systems. “We appreciate Science reporting this particular situation to us and we will be using this report to review and adapt our processes as required.”

…

Google Scholar did not respond to requests for comment.

Leave a reply to fredz777 Cancel reply