A cell line is a population of cells that can be grown in a laboratory culture indefinitely. Cell lines are an essential tool for biomedical research because they allow biological experiments to be performed in vitro (i.e. outside of a living organism). For instance, researchers developing new cancer drugs will certainly test the effect of their drug candidates on many different cancer cell lines before ever considering testing the drug candidate on live animals, let alone human patients.

Because cell lines can grow indefinitely, one research laboratory or laboratory supplier can take a few cells from their cell line stock and give them to another laboratory for that laboratory to begin culturing their own stock. By far the most popular cell line is HeLa, and the many of thousands of HeLa cell stocks used in biomedical research around the world can all be traced back to the original stock of “immortal” cervical cancer cells taken from Henrietta Lacks in 1951.

One complication of relying on cell lines for biomedical research is that stocks will often become cross-contaminated by other cell lines. For instance, HeLa is extremely aggressive as cancer cell lines go and HeLa cells will easily overtake other cell line stocks that are stored nearby. The popular gastric cancer cell line BGC-823 is one such victim of HeLa’s aggression; there are no remaining uncontaminated stocks of BGC-823 and thus it is no longer considered an appropriate experimental model for gastric cancer. The International Cell Line Authentication Committee maintains a register of misidentified cell lines that is currently 582 entries long. A good number of these cell lines were contaminated by cells from a completely different organism, such as human salivary gland cell line CAC2, which is actually made up of unknown cells from a rat.

Because different cell lines can have a wide variety of responses to the same treatment, it is essential that researchers avoid misidentified cell lines and only work with authenticated cell lines that actually represent their system of interest.

Thanks largely to the diligent work of Danielle Oste, now available on bioRxiv [UPDATE: May 16, 2024] now published in the International Journal of Cancer, we can now report on a whole new threat to biomedical research: cell lines that never existed in the first place.

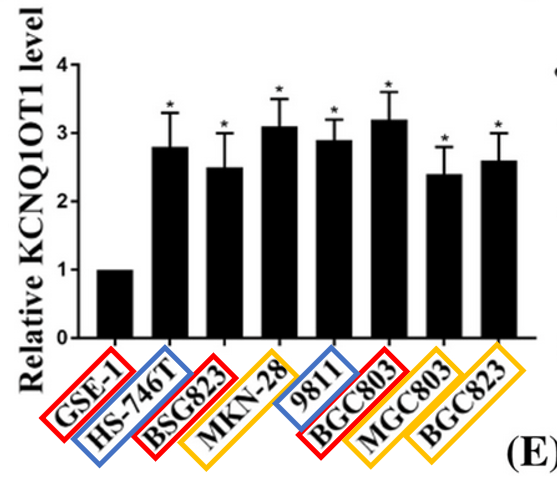

The names of cell lines are usually just a jumble of letters and numbers and thus can often be easily confused. For instance, the name of BGC-823 is very similar to that of MGC-803, another misidentified gastric cancer cell line. One might easily misspell these cell lines as “BGC-803” or “MGC-823”. However, we noticed that sometimes these misspelled identifiers were used to refer to another cell line entirely distinct from these existing cell lines. Take the 2021 article “Long non-coding RNA KCNQ1OT1 promotes the progression of gastric cancer via the miR-145-5p/ARF6 axis” in the Journal of Gene Medicine (Wiley), which refers to experiments in cell lines “BGC-803” and “BSG-823” in addition to experiments in the contaminated cell lines BGC-823 and MGC-803.

Hundreds of articles have referred to experiments in these cell lines despite there being no indication that these cell lines actually exist—there are no entries for these cell lines in any cell line indices, they cannot be found in any supplier catalogs, there are no articles describing how these cell lines were established, and no one seems to have produced any genetic profiles of these cell lines to confirm their identities. We identified eight such “miscellings”: BGC-803, BSG-803, BSG-823, GSE-1, HGC-7901, HGC-803, MGC-823 and TIE-3. There are certainly many more non-verifiable cell lines out there.

Could these cell lines actually exist? It is possible, and we would love to see evidence of it, but it seems much more likely to me that each of these identifiers were born as typos before assuming a life of their own in the scientific literature due to the sloppy fact-checking of paper mills.

Because of non-verifiable cell lines and cell line contamination, the biomedical literature abounds with experimental results that are entirely irreproducible by other scientists, wasting the time of editors, peer reviewers and researchers alike as well as the public funds that support this research.

To learn more, you can check out Jennifer Byrne’s guest post in Retraction Watch or read our preprint [UPDATE May 16, 2024] newly-published paper:

Danielle J. Oste, Pranujan Pathmendra, Reese A. K. Richardson, Gracen Johnson, Yida Ao, Maya D. Arya, Naomi R. Enochs, Muhammed Hussein, Jinghan Kang, Aaron Lee, Jonathan J. Danon, Guillaume Cabanac, Cyril Labbé, Amanda Capes Davis, Thomas Stoeger, Jennifer A. Byrne. Misspellings or “miscellings”-non-verifiable cell lines in cancer research publications. Int J Cancer. 2024; 1-12. doi:10.1002/ijc.34995

Leave a comment